National Day for Truth and Reconciliation

September 30 marks the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation in Canada. Learn about the history of the territory, read the Library's land acknowledgement, and explore resources from our digital library.

Please note: All branches will be closed on Sept. 30 to reflect and honour residential school survivors, their families, and communities.

The Story of the Territory

The following provides an overview of the history of the territory in which Richmond Hill Public Library current operates:

- Current Status

-

Richmond Hill is one of nine municipalities that form the Regional Municipality of York. It became a city in 2019, after having become a town in 1957, and an incorporated village in 1872. It sits 23km north of Lake Ontario.

The 2021 census notes a population of 202,022 residents. The 2016 census shows an ethnically diverse community, and notes Richmond Hill’s population to be comprised of people with the following ethnic origins: Chinese (30.2 per cent); Iranian (11 per cent); Italian (9.9 per cent); South Asian (7.7 per cent).

- Pre-Contact

-

Historical records note First Nations peoples living in the territory in which the City of Richmond Hill currently sits dates back 11,700-12,000 years to the end of the last Ice Age. Evidence of First Nations occupation, which includes five longhouses, can be found in the Oak Ridges Moraine, on the east side of Lake Wilcox where they are estimated to have been built sometime between 1280 and 1320 CE.

There are also records to show an Iroquoian village situated at the southwest corner of Yonge Street and Major Mackenzie Drive, the site was discovered by David Boyle who became one of Canada’s top archaeologists.

- Contact

-

Contact between the Huron-Wendat peoples and French explorers is noted to have occurred in the early 1600s. In 1648, the Haudenosaunee pushed into the territory, defeating the Huron-Wendat and dispersing the remaining citizens eastward towards what is now the eastern region of the province of Quebec. By the late 1600s, the Haudenosaunee began to leave their settlements and the Anishinaabe peoples – including the Mississaugas – began migrating to the territory from their settlements in the Lake Superior.

- Settlement

-

In the later part of the 1700s, the Crown commissioned three roads in the territory that would serve as a military communication route to defend Upper Canada from the French and the Americans. One of the three roads is the now famed Yonge Street, which was designed to connect Lake Ontario and Lake Huron. Early settlers to the newly developed territory included Loyalists, Pennsylvania-Germans, British immigrants, and a small number of African Americans who escaped enslavement, who all migrated to the area to farm.

In 1787, the Crown met with the Mississaugas at the Bay of Quinte to discuss a purchase of the “carrying place” from Toronto to Lake Simcoe in exchange for trade goods that were distributed to the Mississaugas at three different locations across southern Ontario.

These discussions were later framed as “the sale of Toronto”, that had allegedly occurred in exchange for the £1,700 of presents. Much later, research into the “sale” found that the deed was blank – with no reference to a sale – with the markings of three Mississauga Chiefs from the territory north of Lake Ontario on separate scraps of paper that were sealed to the blank deed.

- Treaties

-

In 1805, Mississauga leaders met with Crown administrators and entered into Treaty 13 agreement, also known as the Toronto Purchase. Treaty 13 transferred roughly 1,015 km2 from the Mississaugas to the local non-Indigenous government. Treaty 13 covers a large part of Richmond Hill, with a smaller part in the city’s northeast area is covered by the Williams Treaties that were signed in 1923. The Williams Treaties are noted as being the last historic land cession treaties in Canada and saw the transfer of more than 20,000 km2 of land in what is now the south-central region of Ontario to the Crown.

- Recent History

-

In 1986, the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation initiated a land claims settlement process with Canada to address grievances related to Treaty 13. In 2010, Canada paid $145 million for the lands and affirmed the boundaries of the Treaty as it was laid out in an 1805 survey which included the Toronto Islands. In 2015, the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation filed the Rouge Tract Claim with Canada and Ontario governments to seek the return of the lands – which currently remains outstanding.

Land Acknowledgement Toolkit

Land acknowledgements bring recognition, honour and respect to Indigenous Peoples as the original and long-time stewards of a particular region or territory. Learn about the purpose and how to create one with this toolkit. Visit the Mission, Vision, and Values section of the website for information on the library's land acknowledgement.

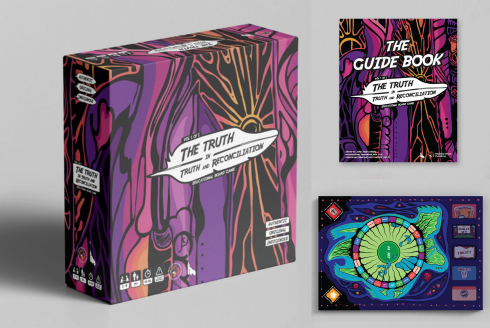

The Truth in Truth and Reconciliation Game

The Truth in Truth and Reconciliation Educational Board Game is a powerful resource to start conversations around reconciliation from an Indigenous point of view. Developed by James Darin Corbiere (Waabi Makoohns) Anishinaabe, Bear Clan, this educational board game includes a guide book, and graphic novel written and illustrated by Corbiere for further learning opportunities. Suitable for ages 14+.

Indigenous Wellness Videos

LifeSpeak is a digital wellness platform with expert content on physical and mental health, including themes around Indigenous mental health, allyship, and creating culturally safe environments. Available for free with your library membership.

Resources for Educators

Explore resources for children and teens on Indigenous cultures, issues, and perspectives. Find books, lesson plans, and digital resources like Explora Canada for students in primary and junior-middle grades. Read about treaties in Ontario and other supporting educational materials.

About Truth and Reconciliation

- The United Nation's Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

-

On June 16, 2021, the Parliament of Canada passed The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (formerly Bill C-15). The Act received Royal Assent June 21, 2021, and was preceded by decades of advocacy by our Indigenous community.

The Act sets out Canada’s obligation to uphold the human rights (including Treaty and inherent rights) of Indigenous peoples affirmed by the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UN Declaration). These include the right of self-determination and the right to have Treaties respected and enforced.

The UN Declaration contains the international human rights standards that Canada and all members of the UN have affirmed, and re-affirmed, many times.

- About the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation

-

In 2021, the federal government passed legislation to observe September 30 as a federal statutory holiday called the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

The establishment of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation is in response to the 80th call to action in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action.

Call to Action #80. We call upon the federal government, in collaboration with Aboriginal peoples, to establish, as a statutory holiday, a National Day for Truth and Reconciliation to honour Survivors, their families, and communities, and ensure that public commemoration of the history and legacy of residential schools remains a vital component of the reconciliation process.

- The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC)

-

The official mandate of the TRC is found in Schedule "N" of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, which includes the principles that guided the commission in its important work.

- Between 2007 and 2015, the Government of Canada provided approximately $72 million to support the TRC's work. The TRC spent six years travelling to all parts of Canada and heard from more than 6,500 witnesses. In addition, the TRC hosted seven national events across Canada to educate and engage the Canadian public about the history and legacy of the residential schools' system and to share and honour the experiences of former students and their families.

- The TRC created a historical record of the residential schools' system, and as part of this process, the Government of Canada provided over five million records to the TRC. All of the documents collected are kept by the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation at the University of Manitoba.

- In June 2015, the TRC held its closing event in Ottawa and presented the executive summary of the findings contained in its multi-volume final report, including 94 "calls to action" (or recommendations) to further reconciliation between Canadians and Indigenous peoples.

- In December 2015, the TRC released its entire six-volume final report. All Canadians are encouraged to read the summary or the final report to learn more about the terrible history of Indian Residential Schools and its sad legacy. To read all six-volumes of the reports, visit your nearest RHPL or visit the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.

- The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement

-

One of the elements of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement was the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada to facilitate reconciliation among former students, their families, their communities and all Canadians.

More than 150,000 Indigenous children were removed and separated from their families and communities to attend residential schools. While most of the 139 Indian Residential Schools ceased to operate by the mid-1970s, the last federally-run school closed in the late 1990s.

In May 2006, the Settlement Agreement was approved, and the implementation of the Agreement began in September 2007-with the intent to bring a fair and lasting resolution to the legacy of the Indian Residential Schools.

Bringing closure to the legacy of Indian residential schools lies at the heart of reconciliation and a renewal of the relationships between Indigenous peoples who attended these schools, their families and communities, and all Canadians.

- The Story of Orange Shirt Day

-

Orange Shirt Day is a legacy of the St. Joseph Mission (SJM) Residential School (1891-1981) Commemoration Project and Reunion events that took place in Williams Lake, BC, Canada, in May 2013.

The events were designed to commemorate the residential school experience, to witness and honour the healing journey of the survivors and their families, and to commit to the ongoing process of reconciliation.

Orange Shirt Day is a legacy of this project. As spokesperson for the Reunion group leading up to the events, former student Phyllis (Jack) Webstad told her story of her first day at residential school when her shiny new orange shirt, bought by her grandmother, was taken from her as a six-year old girl.

The date was chosen because it is the time of year in which children were taken from their homes to residential schools, and because it is an opportunity to set the stage for anti-racism and anti-bullying policies for the coming school year. It is an opportunity for First Nations, local governments, schools and communities to come together in the spirit of reconciliation and hope for generations of children to come.

(derived from The Orange Shirt Day website).

Partner Programs and Booklist

View programs from our partners at Miskwaadesi Studio and explore books they selected to highlight Indigenous voices and perspectives that speak to Truth and Reconciliation. Featured titles below.